Some Thoughts on Sentence Diagramming

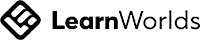

Perhaps you’ve heard of sentence diagramming. You take a sentence and map it using a set of rules that makes the end result look a bit like a confusing road map:

This sentence reads, “During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the city of Bologna had many tall towers.”

Diagramming used to be all the rage in education. In the 1950s and 60s, it was still commonly taught in high-school English classes. These days, it’s mostly home-schoolers who practice diagramming. So why does the art of diagramming have such a bad reputation? Why, for instance, in a popular history of sentence diagramming, does the author claim, “It’s debatable whether diagramming did anyone much quantifiable good. . . . I’m convinced that diagramming was no help to me at all as a writer” (Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog, 150-51)? Why such a dramatic conclusion?

The main reason is that attitudes to the teaching of grammar have changed. Talk to many an expert educator and they’ll say, what’s the point of learning rules when it is so much more effective to just be immersed in language? Let the kids read and write and they’ll pick up the rules intuitively.

Of course, you wouldn’t say that about math – just let the students loose and they’ll figure it out! But when it comes to grammar, at least in North America, high-school students rarely learn anything anymore about how a sentence works. They come to college or university without a clue about how to find a subject. Many can’t identify an adverb or define a clause.

Now, the teaching of grammar can of course be overdone. Learning countless rules can make language arts into a soulless exercise. Yet done properly, some attention to sentence structure is a surely a good thing. I often compare the structure of a sentence to the engine of a car. Not everyone needs to become a mechanic, but we all benefit from having some basic knowledge of the different parts.

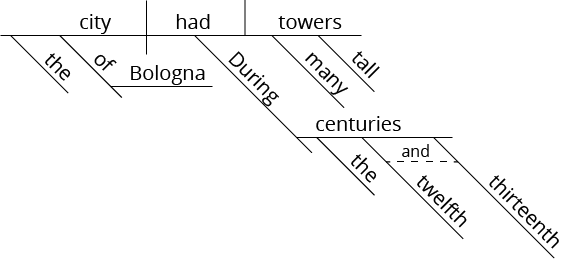

In addition, sentence diagramming is actually not that difficult, as a quick demonstration will show. At their core, English sentences consist of one or more clauses. Each clause contains at least a subject (someone or something doing the action) and a predicate (the action and anything else that states something about the subject. As a result, the simplest sentences contain just two words:

Diagramming used to be all the rage in education. In the 1950s and 60s, it was still commonly taught in high-school English classes. These days, it’s mostly home-schoolers who practice diagramming. So why does the art of diagramming have such a bad reputation? Why, for instance, in a popular history of sentence diagramming, does the author claim, “It’s debatable whether diagramming did anyone much quantifiable good. . . . I’m convinced that diagramming was no help to me at all as a writer” (Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog, 150-51)? Why such a dramatic conclusion?

The main reason is that attitudes to the teaching of grammar have changed. Talk to many an expert educator and they’ll say, what’s the point of learning rules when it is so much more effective to just be immersed in language? Let the kids read and write and they’ll pick up the rules intuitively.

Of course, you wouldn’t say that about math – just let the students loose and they’ll figure it out! But when it comes to grammar, at least in North America, high-school students rarely learn anything anymore about how a sentence works. They come to college or university without a clue about how to find a subject. Many can’t identify an adverb or define a clause.

Now, the teaching of grammar can of course be overdone. Learning countless rules can make language arts into a soulless exercise. Yet done properly, some attention to sentence structure is a surely a good thing. I often compare the structure of a sentence to the engine of a car. Not everyone needs to become a mechanic, but we all benefit from having some basic knowledge of the different parts.

In addition, sentence diagramming is actually not that difficult, as a quick demonstration will show. At their core, English sentences consist of one or more clauses. Each clause contains at least a subject (someone or something doing the action) and a predicate (the action and anything else that states something about the subject. As a result, the simplest sentences contain just two words:

Note how we placed the subject on the left side of the dividing line and the predicate on the right. This is the first step in any sentence diagram.

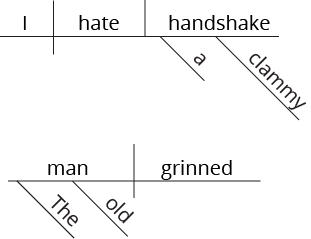

After that we can do all sorts of things. For instance, we can insert a direct object after our verb. Or we can add a bunch of descriptive words (adjectives) on slanted lines underneath:

After that we can do all sorts of things. For instance, we can insert a direct object after our verb. Or we can add a bunch of descriptive words (adjectives) on slanted lines underneath:

In short, diagramming is about stripping down the sentence (the engine) in order to understand how each part is related to the rest. No doubt it’s not for everyone. In fact, our regular writing guide does not teach diagramming rules at all. However, for others, diagramming is a revelation. It makes sense to them, perhaps because they love structure and order.

For that reason, one of our projects this year is to add a standalone course on sentence diagramming. It will cover everything from parts of speech to longer phrases and clauses. If you would like a notification as to when this module is available, send us a note.

When I talk to university students, they often long for more grammar. They’re frustrated that they were taught no rules whatsoever. As the name of our writing guide (The Nature of Writing) implies, the challenge continues to be finding the middle path between being overly rule-bound and writing more organically. There’s no easy solution, but the answer is not to throw up our hands and dispense with grammar entirely.

For that reason, one of our projects this year is to add a standalone course on sentence diagramming. It will cover everything from parts of speech to longer phrases and clauses. If you would like a notification as to when this module is available, send us a note.

When I talk to university students, they often long for more grammar. They’re frustrated that they were taught no rules whatsoever. As the name of our writing guide (The Nature of Writing) implies, the challenge continues to be finding the middle path between being overly rule-bound and writing more organically. There’s no easy solution, but the answer is not to throw up our hands and dispense with grammar entirely.

Work Cited

Burns Florey, Kitty. Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog: The Quirky History and Lost Art of Diagramming Sentences. Melville Publishing House, 2006.

Copyright © 2025